The Conference on the Future of Europe was officially inaugurated on 9 May 2021. In their joint declaration, the three presidents of the EU-institutions spoke of ‘a citizens-focused, bottom-up exercise.’ EU citizens now have one year to feed this digital platform (https://futureu.europa.eu/) with ideas and events at European, national, transnational, and regional level. ‘Digital transformation’ is one of the central issues on which European decision makers ask for feedback from the citizens.

Technology has a major role to play in strengthening the decision making process in modern democracies and in making its outcome more resilient to the challenges ahead, such as climate change and the technological transformation of our economies. There are so many factors to be taken into account but, in all this complexity, it is easy to overlook one key challenge. We know how technology can be used to undermine trust, but we have yet to learn how it can be used to rebuild trust in public life. In this article we will look at one local project in Ireland which offers grounds for hope.

The challenge we face cannot be fully understood without looking at where we have come from. Almost two centuries ago in County Clare in the west of Ireland, Daniel O’Connell was elected to the British Parliament. After a journey of fourteen days, including one sea voyage, he finally arrived and, when he did, he was County Clare at Westminster. He was the sole living link to his constituency and the same was true for many, like himself, who had travelled for a number of days. Those were the days when news travelled slowly and it did so in a world which was a lot simpler than ours. Today all is different and that difference has come about through technology. When a member of parliament gets up to speak, their audience can be anyone anywhere and the response can be immediate. This transformation did not simply happen. It was the result of human ingenuity and effort and, as technology becomes more complex, it also becomes more powerful for good or ill – ‘technology obliges!’.

The Conference will be making extensive use of modern technologies but that is no guarantee of success. It will be structured around feedback from citizens but if this process is only a one-off, it runs the risk of being seen as a passing gesture and nothing more.

Technology clearly has a bigger part to play in the democratic process, but those who are skilled in this area need to remember that they do not begin with a blank canvas.

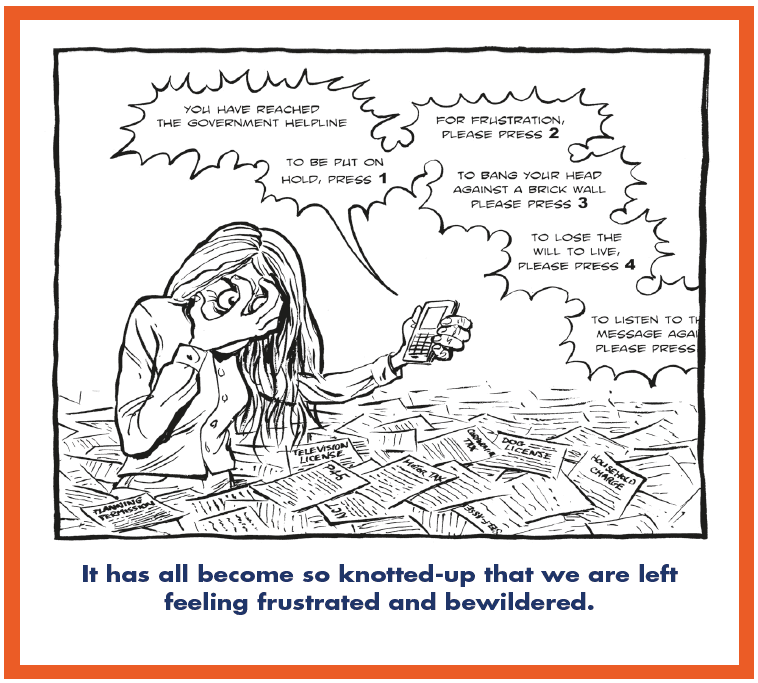

As with finance, technology can no longer be separated from the functioning of government nor from the suspicion to which democratic government has been subject since the 2008 global financial crisis. The EU member states since then have made great strides learning how to work with each other but the growing suspicion of citizens towards government at both national and European level has yet to be remedied. The sense of powerlessness and fear which many experienced in 2008 has not gone away.

All this comes at a time when the challenge of ecological degradation has become increasingly urgent. The circular economy, on which much will depend, will not function without an unprecedented intrusion of government – and technology – into people’s daily lives. Nor will it function if the levels of distrust in government remain as they are. Against this background, the Galway County Jury experience in the west of Ireland offers hope. In March 2013, Galway County Council called for the setting up of a Citizen-Jury ‘to develop practical proposals for public sector reform.’ The Galway County PeopleTalk Jury functioned at a local level. Its members were chosen by lottery from a list of volunteers and the endorsement of the elected local council certainly enhanced their standing. They were given two years to conclude their report, which was a long time but they maintained their focus and energy to the end.

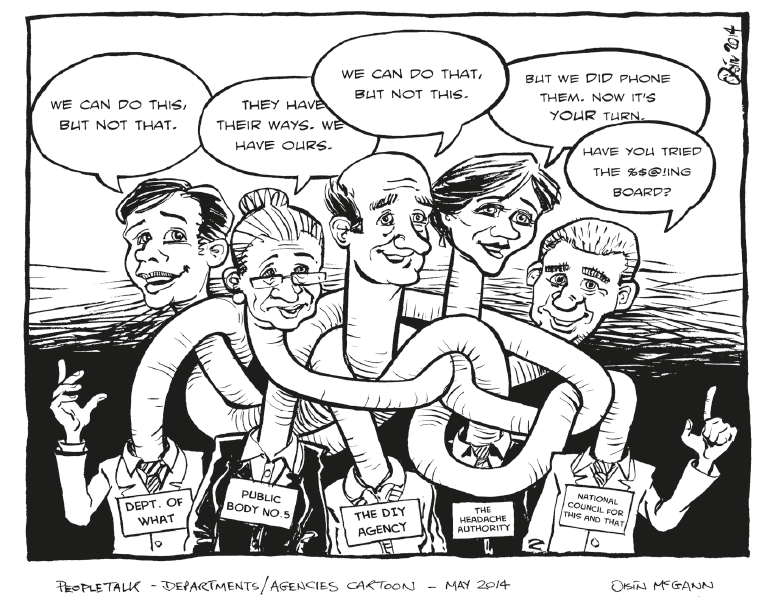

The Galway Jurors quickly let it be known that they knew nothing about public administration, but they were clear about how they wanted to learn. They asked to meet two people working at ground level from each of five state agencies – the local council, the police, the health authority, social welfare and the Irish language authority. These officials, when they met, focused on a particular problem which they described as ‘disheartening’ and which involved an issue of data protection. The Jurors responded with a practical and workable proposal which was largely, though not entirely, implemented.

In opting to hear from ground level public servants, the Galway Jurors were calling on the insights of those officials of the state who engage directly with the lives of citizens. They were familiar and trustworthy figures and they spoke from experience. They knew how policies worked or failed to work at ground level and they had views on what they saw.

If a process similar to the Galway Jury experience were to be tried in different parts of Europe, the jurors would be able to draw from a particular perspective on modern government which has not previously been considered – the experience and insights of ground level public servants. They are unquestionably ‘ordinary citizens’ yet no one is able to observe as closely as they do, the functioning of government at ground level.

If this model were to be adopted, public service managers would be seen to show a conscientious willingness to be confronted by challenging questions. On its own, a Citizen Jury will not be well-placed to pose such questions, but this is where the ground level public servants can make a contribution by speaking, from within the structures, of ground level realities to which those in management positions have no direct access.

In talking of a bottom-up approach, those who initiated the Conference on the future of Europe have acknowledged that their own perspective is limited. The bottom is furthest away from the top, but how do we measure the distance? One way is through the prism of trust and its absence. ‘The bottom’ includes those who have little or nothing and who live in perpetual deprivation, but there are many whose lives are comfortable enough but who have no desire to engage with politics or politicians. In their eyes, talk of a ‘bottom-up’ approach is just another piece of bureaucratic jargon. Their attitude may be cynical but cynicism walks hand in hand with anger and disillusionment. It can easily turn to hostility and obstruction.

If the trust of citizens in public life is to be restored, we will need a kind of public drama in which ‘ordinary citizens’ are seen to speak and be heard. The ‘ordinary citizen’ is not an abstraction. They have families, neighbours and stories to tell, and the surest way to identify them in the public forum is to empanel a Citizen-Jury at local government level. As well as being local, they will need a clear time frame to ensure a recognisable outcome.

Government, including elected politicians and public service managers, will have their part to play in this drama. However, without a contribution from the worlds of technology and ecology, the role of government will be seen as remote. It is good that both these networks accept the need to dialogue with each other and with social realities but, as with government, they also need to win the trust of the wider population.

After his election, Daniel O’Connell was seated on a chair, which was lifted high and carried from the town of Ennis to Limerick City, a journey of fifty kilometers. Many of those who carried him would have had no vote and no possibility of getting one, but they had hope and energy and they were participating in the political process. The ultimate test of the Conference on the Future of Europe will lie in its capacity to awaken that kind of hope and energy. Hope is fed by specific moments and activities which people can identify and celebrate.

Technology can help shape those moments but only if those skilled in this area can accept that their responsibility is no different to that of elected political leaders. They too can abuse their power. They too can enhance the power of the people, but that calls for political intelligence. If they really want to lead, they must look beyond their existing supporters to those at ‘the bottom,’ whose trust in all leadership is low. If, by working with political leaders and citizens, they find out what is missing, and how to remedy it, we will all see an awakening of hope, energy and new possibilities. The Galway experience offers hope but only if it is replicated throughout Europe. Those newly established Citizen-Juries, scattered across the European Union, will have to find a way to be present to each other like Daniel O’Connell when he made county Clare present in Westminster. To achieve that, technology will be a crucial need.

Edmond Grace

Secretary for Justice and Ecology,

Jesuit European Social Centre (JESC).